The breakdown with Frank Mecca

It’s time to update the CalWORKs Earned Income Disregard

Let’s start off with the basics, what is the Earned Income Disregard and how does it work?

When the Legislature – on a bipartisan basis – implemented CalWORKs, which is California’s version of federal welfare reform, there were several key tenets; one of them is that work should pay. The idea is that as families on CalWORKs are able to move into the workforce and earn money, we won’t deduct dollar-for-dollar from their CalWORKs check. Rather, they would be allowed to keep a part of their CalWORKs check, a part of their earnings, and they would keep supportive services like child care and transportation so they could gradually ease their way off CalWORKs. The intent was that by the time they exited the program they were sufficiently stable and had enough resources to be able to leave CalWORKs and not come back on. It was a way to incentivize work.

The Legislature created the Earned Income Disregard (EID) as the primary vehicle for making work pay. The EID essentially allows the client to keep $225 of their earnings every month and then 50 percent of everything above $225 until their income gets to such the point that they would no longer need to be on CalWORKs. It’s intended to be a gradual transition off assistance, or a bridge from CalWORKs to self-sufficiency.

When was the EID last updated?

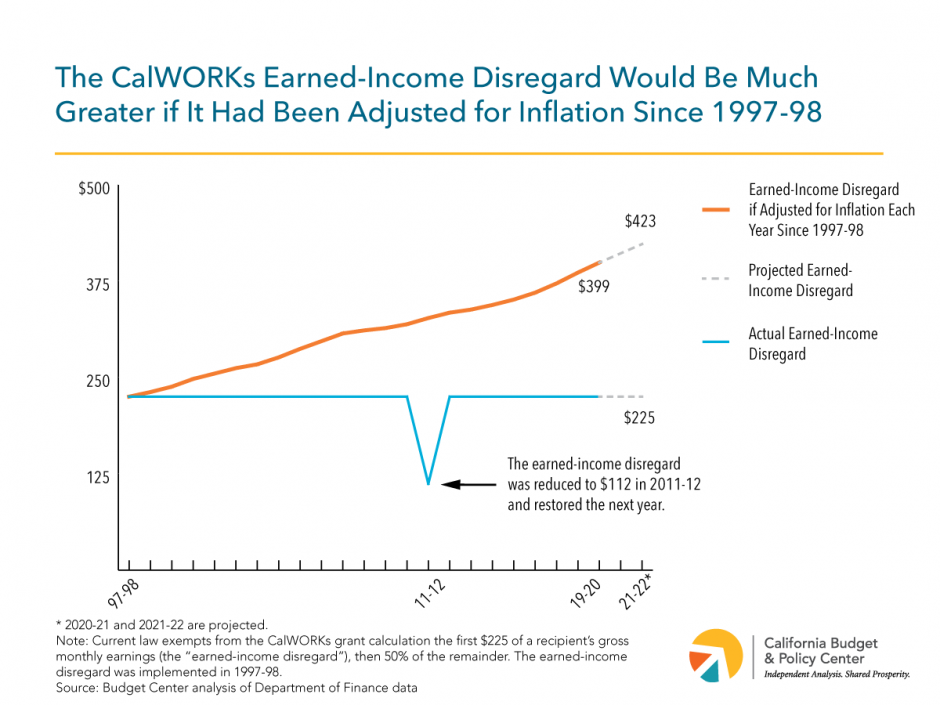

It actually hasn’t been updated since the program was created in 1998. In fact, it was cut during the recession. The value of it was reduced as a budget-saving mechanism during a time when the state was having deep budget deficits. It’s since been restored, but only to the level that it was created in 1998. So, it has not been updated for inflation, increases to the minimum wage, or anything else for that matter, since 1998.

“The EID is no longer a bridge, it’s now more like a cliff.”

How will increasing the EID help families in the CalWORKs program?

Let me give you an example: a family in 1998 at full-time minimum wage employment would have their earnings from employment, they would have a small CalWORKs grant, and they would have supportive services from CALWORKs. They would not have earned enough money at minimum wage to be denied aid. That same family today would be off of aid and services, meaning they would be losing about $250 per month. In other words, we are pushing people off the CalWORKs program now more precipitously. The EID is no longer a bridge, it’s now more like a cliff. That’s because as inflation and minimum wage have gone up, we haven’t changed the incentive, so the work incentive that bipartisan policy makers agreed to two decades ago has significantly eroded over time. As a result, we are pulling the rug out from underneath CalWORKs recipients before many of them are ready to be self-sufficient.

By our calculations, if policy makers had kept the 1998 Earned Income Disregard updated for inflation and minimum wage – not increasing the generosity of it, but just indexing it with cost of living – it would be $500 plus 50%. As the minimum wage is scheduled to go up in California, the value of the EID will continue to erode, which creates a terrible catch-22 for a family.

“We are pulling the rug out from underneath CalWORKs recipients before many of them are ready to be self-sufficient.”

For example, supports that CalWORKs provides someone like transportation support, books and tuition assistance, child care, etc. are important to help someone work and support their family, but if they take that extra shift, they could be pushed off the program. They would lose a modest amount of their grant and lose work supports. Does that person take the extra work and have a very precarious transition off the program, or does she turn the shift down and inhibit her development as an employee? It’s an awful catch-22 that we leave for clients.

Additionally, we didn’t have the housing affordability crisis in 1998 that we have right now. We know that rents have risen three times faster than wages and inflation. It’s arguable that the EID that existed in 1998 ought to be more generous today as opposed to just as generous for this reason. The proposal that CWDA is putting forward would restore the Earned Income Disregard to the incentive level that existed in 1998, but that was when rents were far more affordable for low-income people. Our proposal is extremely modest because it doesn’t account for the changes in the housing market, so this is just a step in the right direction. Housing affordability has made the precarious transition from welfare to work that much more precarious.

What would cash-in-hand mean for these families and what does the research say?

$250 for a low-income family means supplies for kids at school, or for the rent increase that’s going to be the difference between being housed or homeless. Perhaps it seems like a small amount to people who don’t experience what low-income people do, but it’s often the difference between keeping a roof over the head of their children and a minimally decent standard of living or living in your car and having your child denied basic elements of life – extra-curricular activities or a tutor to help them with a problem at school.

The research is conclusive on what poverty does to the brains of children. We know about the poor health, educational, employment – you name it – outcomes for children that live in poverty. What the research is also telling us that if you give low-income families cash, you give them resources, they spend it on their children and their children’s wellbeing is better. Whether it’s their school development or their health development, there’s emerging research that says cash really matters to the healthy development of children in low-income families.